Ecological Research

Within this broad field our team provides a wide range of ecological research, both commercial and non-commercial, all in-house. As part of EcIAs or, for example, as part of routine work for designated conservation areas, we carry out ornithological surveys, protected mammal surveys including bat surveys, reptile and amphibian surveys, invertebrate surveys including freshwater pearl mussel surveys, National Vegetation Classification (NVC) surveying, Phase 1 Habitat surveys and specific botanical surveys.

Further specific applications have included, for example, turnover of juvenile Golden Eagles based on DNA studies; reintroduction potential of freshwater pearl mussels to rivers; development of methods for surveying nocturnal mammals; the distribution of rare flowering plants in maritime heath; etc.

We also set aside a proportion of funds each year in order to fund our own non-commercial research, of importance to wildlife conservation, which would otherwise not be funded. This has included work on globally important seabird colonies, hen harrier habitat preferences in Ireland and research into the UK's most important population of the globally threatened freshwater pearl mussel and climate change impacts on this species.

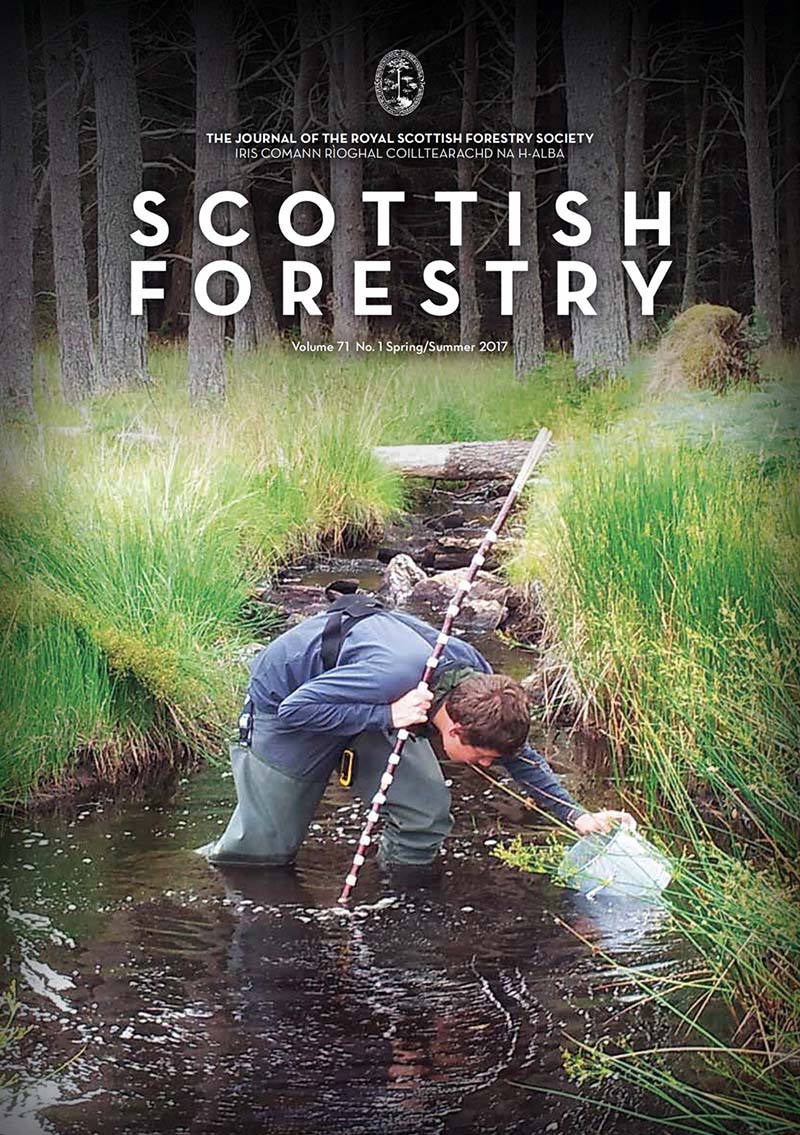

From Scottish Forestry Volume 71 No. 1 Spring/Summer 2017 – Figure 1: Surveying a small previously unsurveyed watercourse in Catchment A. Pearl mussels were discovered in this watercourse in 2013.

From Scottish Forestry Volume 71 No. 1 Spring/Summer 2017 – Figure 1: Surveying a small previously unsurveyed watercourse in Catchment A. Pearl mussels were discovered in this watercourse in 2013.

Figure 1 Whimbrel chick © Digger Jackson

Figure 1 Whimbrel chick © Digger Jackson Figure 2 Whimbrel adult habitat with nest in foreground © Digger Jackson

Figure 2 Whimbrel adult habitat with nest in foreground © Digger Jackson Figure 3 Whimbrel nest © Digger Jackson

Figure 3 Whimbrel nest © Digger Jackson Figure 4 Whimbrel chick habitat © Kate Massey

Figure 4 Whimbrel chick habitat © Kate Massey Golden Eagle © Alba Ecology

Golden Eagle © Alba Ecology Figure 1. Royal Tern Thalasseus maximus and Caspian Tern Hydroprogne caspia colony, Tanji River Bird Reserve, Gambia, April 2012 (Donald Shields)

Figure 1. Royal Tern Thalasseus maximus and Caspian Tern Hydroprogne caspia colony, Tanji River Bird Reserve, Gambia, April 2012 (Donald Shields)